Everybody likes to think they output good quality code, but how do you ensure that whilst making sure that your team members are on the same page? Here’s a few techniques that I’ve used over the years. This blog is mostly aimed at team leads or seniors working with 3+ people, but some may tips be useful for single contributor/OSS projects.

Formatting & Consistency

Personally, I’m super pedantic about the formatting in my code. Even just errant or missing spaces a bugbear, but thankfully there are tools to prevent this sort of general annoyance.

Code style rules

The first step is to make sure that your team are all reading from the same hymn sheet. Some may be more strident about consistency than others, but at the very least you should choose a code style and stick with it. For many, just using the default IntelliJ/Android Studio code style is enough; many use the Google Java code style.

Regardless of whether you use the default or some crazy custom settings, why not simplify everyone’s lives and bundle your settings with your project’s git repo? This saves you digging around IntelliJ’s preferences when onboarding a new team member, and provides one less excuse for those not adhering to standards.

Bootstrap

Better yet, why not have your project install your code style for you? This idea is shamelessly lifted from the excellent Kickstarter app, where they have a scripts folder which contains a bash file which sets up the project for you - copying across their code style xml, removing the default file header, running git submodule update --init --recursive, and even checking for the presence of their keystore and warning the user if it’s not found.

We’ve made use of this idea on the Blockchain Android app, and it makes onboarding new developers and contributing to the open source repo much easier. Alternatively you could probably write this as a Gradle build script too if that’s more your thing.

Android Guidelines

IntelliJ/Android Studio’s formatting rules can only get you so far - what about formatting for RxJava operators? Resource naming conventions? Do you want your team using conditionals without braces?

For this, I recommend that you write or fork a more complete style guide, such as the excellent one by the Ribot team. This leaves no ambiguity as to how you expect your team to write your code, and I leave a version of it that I’ve edited pinned to Chrome to refer to whenever I forget something silly. Recently we started using Kotlin in production but I found the official guidelines a bit lacking, so I wrote a basic guideline for that too. Link to these guidelines in your README.md and never have an argument about line wrapping again.

Enforcement

So you’ve done all of this but you want to make sure that people are actually sticking to the rules you’ve laid out - how do you go about it?

Thankfully there are tools out there which allow you to validate this stuff. Checkstyle is the most commonly used tool for this; just ensure that the checkstyle task is being run in CI (you do have CI, don’t you?) and that it fails the build when necessary.

You may find initially that getting builds to pass is pretty painful, as you might have to edit some rules to enforce your own style choices. Consequently, we’re not currently using it at Blockchain, but I would 100% use it on a new project if given the chance.

Robustness

What good is pretty, consistent code if it breaks or can’t be maintained? How do you make sure that your code is relatively robust?

Testing

Testing on Android used to be an absolute nightmare. Nowadays, it’s comparatively simple assuming you’ve chosen a sensible architecture and maintain reasonable design choices such as inversion of control. Consequently there’s no excuse for not having tests: they promote confidence in your code, catch edge cases you might not have designed for (if the tests are well written) and it’s just generally gratifying to see your coverage go up.

You should run unit tests on CI whenever code is pushed to a remote branch. This helps catch bugs during the development process and ensure that nothing too scary gets pushed to master. In that vein, we also have it set up so that a different CI server runs integration tests on creating a pull request into either develop or master. As these are slower, we don’t want necessarily want them running on every push.

We also make use of protected branches, which prevents a lazy developer from force pushing to master, and won’t allow us to merge PRs until all checks have passed (unit & integration tests, plus code coverage via Jacoco + Coveralls.io).

Architecture

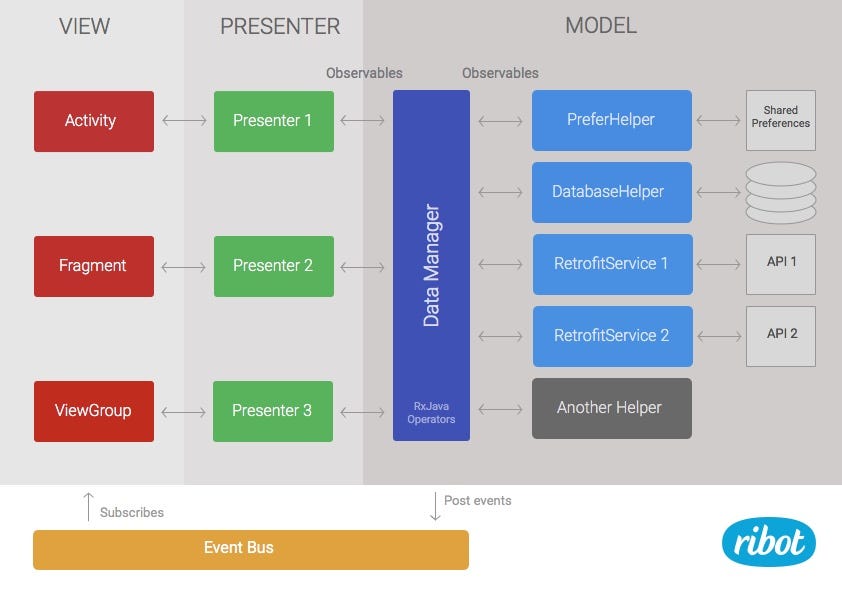

For a testable app, you’ll want to be using some form of architecture convention, such as MVP, MVVM, MVI, Redux or whatever your preferred way is. This helps separate the Android layer (which is very difficult to test) from the core business logic, and if done sensibly can make a huge difference in making the app more testable. We use MVP at Blockchain (although you can see here that we’re moving away from MVVM).

We also make heavy use of Dagger2, which has a pretty steep learning curve but makes handling the creation and injection of your dependencies much easier, and therefore makes testing simpler. I would definitely recommend spending some time learning how to use it.

Again this is where having a company guideline linked in your repo is probably the simplest way to make sure the team is adhering to your architecture. Referring back to Ribot, their style guide also includes an awesome architecture diagram as well as their reasoning as to why they chose the layers and structure that they did. If you’re thinking about switching to something like MVP, write out a similar diagram as you may find it helpful, then get coding a simple example for the team to refer to.

Bugs

Of course, testing only gets you so far; there will be plenty of bugs that you might not have spotted. Here again, there are tools to give you a hand. Lint is a big one, and this can be run from the command line (and therefore CI) and output the results for you. You can also customise your lint rules should you so want, and again bundle them in your repo.

You should aim to reduce the number of lint errors that you see at build time, but for years this was quite difficult to enforce as either a single error would fail your build, or you simply added lintOptions.abortOnError false to your build.gradle. Mercifully, the Android team has added a tool to allow you to set a baseline and save that in your repo - meaning that from that point forward, any new errors results in build failures.

The downside is that Lint only runs when you’re generating a release build, and when you’re under pressure to get a build out to QA or what have you, that might not be the best time to have to fix errors. The solution is simple: add a Lint task to your CI process (are you noticing a pattern yet?). It’s as simple as ./gradlew lint, although saving the output is going to vary based on your CI provider.

Another excellent tool is FindBugs, which spots all sorts of issues related to security, performance and general code correctness. It’s a fantastic tool which I’m ashamed to admit I haven’t added to CI yet, but is run manually at least once a month to get a feel for general code correctness. I recommend it thoroughly. Again, add any custom filters to your repo so that everyone has access.

Crashes

With all the tools and caution in the world, sometimes bugs will slip through the net. How do we handle those?

Firstly, do not rely solely on the Google Play Store. Bug reports have to be manually uploaded by users, which in my experience means that less that 0.1% of all crashes are ever reported. This will change due to Google’s new stance on the matter (where everything is reported automatically), but you still don’t want to rely on the Play Store dashboard for your bug hunting.

For that I have always used Crashlytics which is exceptional. I’ve also used Firebase’s solution which is so-so, but Firebase/Google now recommend that you switch to Crashlytics anyway, which will be incorporated into their metrics in the coming month. If you don’t currently have a crash reporting library; get this added now and prepare to be humbled.

Kotlin

It wouldn’t be an Android blog without some mention of Kotlin - but in all seriousness; by some estimates 60% of crashes in Android apps are Null Pointer Exceptions. Kotlin’s nullable type handling helps reduce that dramatically, and should be considered for the improvement it can make to your app’s reliability (and overall developer productivity & happiness).

One caveat to this is that many static analysis tools don’t currently work with Kotlin, and Lint itself has less checks. I expect this will change in the next six months though, as the language explodes in popularity and Google throws their weight and expertise behind it.

Other tools

Sonarqube is another well-established tool that attempts to provide you with an overview of your code’s quality. It gives you a measure of technical debt, code coverage, code smells and a bunch of other useful metrics. I can’t speak to it’s quality, but it’s something that I’d like to integrate at some point.

Of course, your main line of defence in ensuring that good code goes out to your consumers is peer review. Much has been written about how to go about reviewing the code of others so I won’t say much here, other than you absolutely need to make pull requests a key part of your programming workflow if you don’t already. Linus’s Law states:

Given a large enough beta-tester and co-developer base, almost every problem will be characterized quickly and the fix obvious to someone.

Or more succinctly: given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow. Although there won’t be many eyes if you work by yourself, giving yourself a “cooling off” period between writing a PR and merging it can be invaluable too.

This workflow also allows you as a team lead to keep an eye on the performance of each team member and help out those that are struggling, allows Juniors to learn from the Seniors and should be a level playing field for all where ideas and notes are exchanged, not judgements levied.

You may not want all to use all of the ideas I written about here, but I’m hoping that some of you found this useful. Go forth and create beautiful, consistent, reliable code!